Slavery

SOUTH CAROLINA, 1850s

Charleston, South Carolina, was a loud and busy place in the 1850s. People selling and trading filled the city’s cobblestone streets. Walking around, you might hear an enslaved woman selling produce or see an enslaved man making furniture. Looking closer, you would notice they wore badges, reading “fruiterer” and “mechanic.” In the city of Charleston, where enslaved people outnumbered white people, the government created a hiring-out system to control the local enslaved population.

If you ventured over to Chalmers Street, you might see the slave auction advertisements of Louis DeSaussure or Alonzo White. These men sold people at Ryan’s Mart, a slave auction house. Thousands of enslaved people, being bought and sold, passed through Charleston on their way to places throughout the South.

Valued, Sold, and Controlled

In Charleston, slavery was big business and a part of everyday life. Jane, age 12. Mitchel, age 15. Clarinda, age 13. Auctioneers at Ryan’s Mart sold these three and thousands of others during the mid-1800s. Slave auction house advertisements often highlighted the skills of those for sale and placed a monetary value on each person.

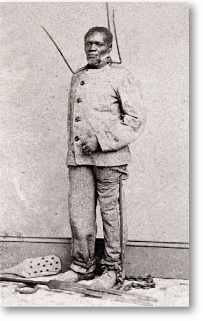

Charleston enslavers could rent out slaves to work as servants, street peddlers, porters, and mechanics. The city required enslavers to register their slaves for hire. Each registered slave wore a tax badge, usually on a string or chain, and had to show it to any white person who asked to see it. Each badge number represented the order in which the person was registered in a particular year and job category. Some white workers resented this system as unfair competition. White workers demanded much higher wages, making slave labor attractive to employers. But enslavers often permitted enslaved people to keep a small portion of their earnings, giving them a little independence within the harsh system of slavery.

Resistance, Escape, and Punishment

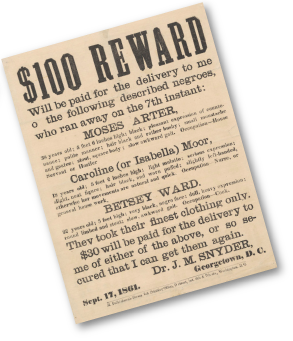

Some enslaved people resisted slavery by working slowly. A few others fought slavery through armed uprisings. Still others tried to escape, risking their lives to be free. In an effort to capture runaway slaves, enslavers frequently put up posters, providing physical descriptions of the runaways and offering monetary rewards for their return.

Runaway slaves, if caught, suffered brutal punishments. Some were forced to wear a heavy iron neck collar, which made it almost impossible to escape again by restricting mobility and making the person instantly identifiable as a runaway.

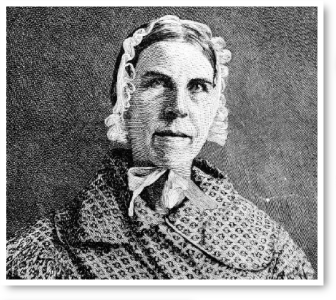

The Fight to End Slavery

Europeans first forced people from Africa to come to the Americas in the early 1600s for slave labor. Slavery spread widely, but by the mid-1800s, most enslaved people in the United States lived in the South.

When it was created in 1787, the Constitution described enslaved people as property. Some Americans believed that slavery was wrong and that it should be abolished, or ended. Known as abolitionists, they fought slavery by organizing, holding meetings, and writing books and newspaper articles. Ultimately, it took the Civil War, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the Thirteenth Amendment to end chattel slavery, or the ownership of humans, in 1865. However, the Thirteenth Amendment does allow slavery in the penitentiary system. Prison authorities can continue to use prisoners as enslaved laborers. This persists as a stain on American freedom ideals.