Japanese Internment

WEST COAST, 1940s

Imagine the United States government imprisoning you and your family. Taken from your home, you are forced to live together in a tiny room made of tar paper and plywood. Barbed wire and gun towers surround you, the guards’ guns pointing in. At six years old, you are suspected of being a spy.

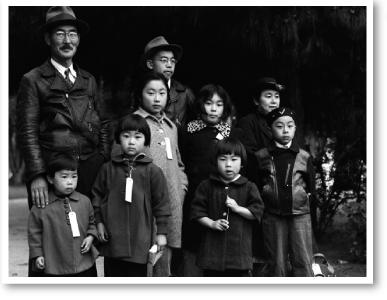

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese military attacked the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Within days, people of Japanese ancestry became the target of hysteria, increased racism, and suspicion. Government officials decided that all people of Japanese descent presented a security threat. During World War II, they forced 110,000 Japanese Americans and immigrants living in the western United States into internment camps, completely denying them of their civil rights.

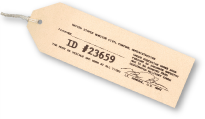

Numbered, Isolated, Questioned, and Trapped

Names became numbers as internees lost their freedom. All interned families received a number and used it to mark their possessions. Government officials established ten internment camps in remote places. They wanted to isolate the internees, whom they viewed as possible spies. While at the camps, internees were forced to take a questionnaire to test their loyalty to the United States. Each day they saw the rest of the world through barbed-wire fences.

Making a Life in the Internment Camps

Internees often gathered odds and ends to improve their tiny living spaces. They transformed rocks, scrap wood, and pieces of fabric into items to provide some comfort and sense of home. To pass the time, many took up crafts, such as carving, sewing, painting, and jewelry making.

Families in the camps also socialized with one another. The game Hanafuda, meaning “flower cards,” was popular among adult Japanese immigrants. Students attended school in flimsy, quickly constructed buildings and tried to recreate activities enjoyed by other American students, such as holding dances, playing sports, and publishing yearbooks.

Acknowledging Injustice

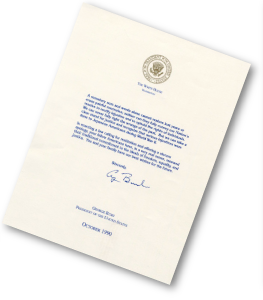

After decades of work by Japanese Americans, the United States government finally acknowledged its complete denial of their civil rights during internment. Former internees typically received a letter from President George H. W. Bush and some monetary compensation.