Pullman Porters

CHICAGO, 1920s

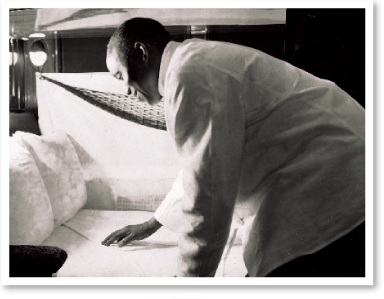

<p>You’ve spent your day on a moving train, working nonstop for 14 hours. You’ve carried suitcases, run errands, made beds, shined shoes, and politely greeted countless passengers, even the rude ones. If you’re lucky, you’ll get four hours of sleep tonight. You are a Pullman porter.</p>

<p>In the 1920s, job opportunities for African Americans were limited. At a time when most worked as sharecroppers or housekeepers, the job of a Pullman porter was highly respected in the black community. Porters had steady work and got to travel around the country. But their friendly smiles and neatly pressed uniforms masked the hardships of the job. Porters clocked 400 hours a month, earned low wages, and could be fired for speaking up about their difficult working conditions.</p>

The Pullman Porter

From its beginning in 1867, the Pullman Company hired only African American men as porters. By the 1920s, the company employed 12,000 black porters, who made the company’s vision of full-service luxury travel a reality. Whatever passengers wanted or needed, porters provided. Every moment of a porter's day was regulated. The company told porters how to interact with customers, which jacket to wear for what job, and how to handle luggage.

Pullman porters took great pride in their work. Their customer service routine—including making beds and shining shoes—was demanding and left little time for rest. To earn a full month’s pay, porters had to clock 400 hours or 11,000 miles, often with little rest. These and other conditions prompted some porters to unionize.

The Fight to Organize

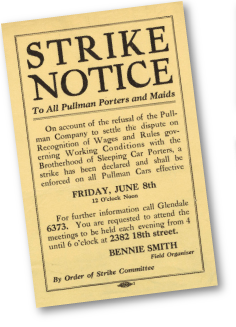

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) was founded in 1925. Union leaders fought to win better working conditions for Pullman employees but met resistance from the company and doubt from the porters. For the first few years, the company ignored the BSCP. Most porters, aware they could be fired for joining, stayed away.

BSCP leaders held meetings at South Side churches and clubs to convince community members that the union would fight for workers’ interests. A. Philip Randolph was the first president of the BSCP. Porters asked him to lead their union because of his strong views on organizing in black communities.

Success for the BSCP

In 1935, the BSCP became the first African American union to receive a charter from the American Federation of Labor and recognition from a major corporation. But in some ways, the union’s work had just begun. The first contract between the BSCP and the Pullman Company took two years to negotiate. It redefined work and rest hours and included a raise.

A Lasting Legacy

The BSCP never had more than 12,000 members. Compared to other unions, it was very small, but its impact was great. The BSCP’s successful battle against the Pullman Company was important for porters and the larger African American community. Union leaders challenged racist stereotypes that depicted black people as incapable of organizing.